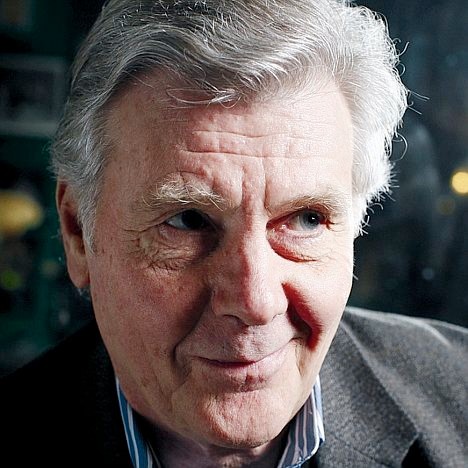

Imagine you are a famous actor, at the top of your game, and have just appeared in a movie with Mick Jagger. And then you give it all up and move to Sheffield to become a travelling salesman. This story has done the rounds since the 1970s and yes, it is all true.

William Fox, born London 1939, was the son of theatrical agent Robin Fox and actress Angela Worthington. He first appeared on film in 1960 in The Miniver Story but was working in a bank when director Tony Richardson offered him a minor role in The Loneliness of a Long-Distance Runner.

Under his stage name, James Fox, he went on to star in The Servant, King Rat, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines and The Chase. Handsome and appealing, Hollywood was calling, but there was a problem.

After playing alongside Mick Jagger in Performance in 1968 (not released until 1970 owing to its sexual content and graphic violence), James Fox was in a crisis.

“There were so many things that caused tension in me,” he said. “Working on Sundays, making love on screen and using bad language.”

The result of this self-torture was that Fox turned to religion. In 1970 he joined a Christian group called The Navigators, his involvement the subject of a BBC documentary, Escape to Fulfilment, in 1971.

“When it was over, I had to decide what to do in the longer term. I had met another Christian, Alan, from near Sheffield, that summer, and we immediately became friends. He was an administrative manager with British Steel at Stocksbridge. He invited me to come north to live with his family.

“I was told that I’d have to get a job, so I bought a copy of the Sheffield Morning Telegraph and sat down in Barker’s Pool to study it. Just about the only job I could see that I could do was as a salesman and there was a vacancy for a post with Phonatas, to get new clients for their office telephone sterilising service in the Sheffield and Rotherham area.

“On my first day at work, I went to London Road. My second stop was a car showroom. The manager interviewed me. ‘You’re James Fox, aren’t you? What on earth are you doing here?’ I told him I wanted him to sign up to have five phones cleaned weekly and that I’d come to live in Sheffield and was doing this as a job. I was given the contract by the incredulous manager.”

For the next eighteen months he toured every business district in Sheffield and Rotherham, the evenings spent making evangelism visits, attending meetings and Bible studies.

Attracted by the estate agency business, Fox moved to T. Saxton and Co, to become an assistant in its commercial property department. During the summer of 1972 he met Mary, a nurse, whom he married the following year and set up home at Oughtibridge.

“I went to the office each day by bus down London Road, which I had walked so many times as a salesman, and in the evening, I came home to my wonderful wife and her cooking.”

After he was offered a chance to join the staff of The Navigators, Fox and his wife finally left Sheffield and moved to Leeds in 1974.

By the early eighties, suitably refreshed, Fox decided to return to acting. The first role he was offered was playing opposite Meryl Street in The French Lieutenant’s Woman, a role he understandably turned down.

In the end, his comeback involved several dramas for the BBC before hitting the big screen again with Greystoke: The legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes, A Passage to India and Absolute Beginners.

Since then, Fox has enjoyed a second career on stage and screen, although often overshadowed by acting brother, Edward Fox.

James and Mary Fox have five children – Thomas, Robin, Laurence (DS James Hathaway in Lewis), Lydia and Jack, the youngest two also capable actors. He is, of course, also uncle to other acting offspring – Emilia and Freddie Fox.

The Sheffield connection may now be forgotten, but when James Fox appeared on Desert Island Discs, he chose Oft in the Stilly Night by the Bolsterstone Male Voice Choir, as one of his eight discs.