No. 1 St James’ Row, better known as Gladstone Buildings, near the Cathedral, opened as the Sheffield Reform Club in October 1885. It was designed by Sheffield architects Hemsoll and Smith for the Gladstone Buildings Company.

At the time, a correspondent said that, “The Liberals of Sheffield were entitled to feel proud of the club, for it was in every respect of high-class character.” The club was altogether distinct from the company which it paid rent, though only a small amount.

The Gladstone Buildings Company had been formed in 1882, chiefly through the exertions of Mr Batty Langley, to provide accommodation for a Reform Club, and to be the headquarters of the Liberal Association.

Alas, following the threat of demolition in 1976, much of its original configuration was lost during late twentieth century renovations, with much of the interior converted into office space.

The rooms of the Reform Club were taken over by Mr J.C. Skinner and the association, soon after completion, and formally opened by the Earl of Rosebery.

The catering arrangements were in the hands of Herman Gadje, the steward, with previous experience of leading clubs in Newcastle, Birmingham and Bradford, the cooking in the charge of a capable chef from London.

A tariff was prepared by which members had the choice of dining at the “table d’hote” or ordering whatever they wanted at fixed prices.

The Reform Club was entered from St James’ Row, through a handsome portico, which communicated by folding doors, with the principal porch, lofty and well-lit. Around the walls of the hall was a dado of Cork marble, edged with polished black marble, and the archway which divided the hall, was enriched with marble pillars.

On the left side of the entrance hall was the porter’s room, and on the right the lavatories and cloakrooms, fitted with every convenience, including private lockers for the members. There was also a letter box in the hall, with the club negotiating with the postal authorities to secure all day collections.

The staircase up to the first floor was lit by lantern and windows – with stained glass soon replacing the semi-opaque windows originally installed. The stairs were covered with Brussels carpet, and the balustrade was wrought-iron and Spanish mahogany.

It reached the dining-room (45ft long by 23ft wide), again carpeted, the walls being decorated with a dado picked out in two colours, and able to accommodate about one hundred people. It was well lit with oriel windows and two large Siemens lights hanging from the roof. A serving room adjoined the dining room and was connected by a serving lobby.

The reading room, adjoining the dining room, had an angled oriel window, with sweeps across the whole of Church Street, the Churchyard, High Street and St James’ Row. It had originally been planned that a balcony might be added around the window, from which political addresses might be delivered.

It was fitted in similar style to the dining room, except that the lighting was affected by several gas brackets fixed to the walls, the furniture including easy chairs, armchairs and settees, whilst the tables were covered with Morocco leather.

Both rooms were separated by a “felted” ornamental revolving partition, carved in panels from solid wood, which could be removed to form one grand banqueting room.

A writing room adjoined the reading room, from which it was divided by a glass partition with a door in the centre, and with a separate entrance from the staircase.

To the left of the staircase was a waiting room, and a smaller room used for telephonic purposes.

Passing upstairs, the visitor reached a mezzanine floor (between the first and second floors) containing two rooms that were used as private dining rooms.

The chief features of the second floor were the billiard and smoke rooms, the former being 45ft long by 23ft wide, also with an oriel window at the centre. The original intention had been to place three full-sized billiard tables (made by Cox and Yeman) here, but due to possible overcrowding, the third table was instead sited in the smoke room.

Adjoining the smoke room was a smaller room, to be used for smoking and card purposes, and eventually used as the reference library, supplied with all the leading daily, weekly and monthly newspapers and magazines.

The mezzanine floor also contained a committee and secretary’s room, and a steward’s room, with a safe to store silver plate and valuables.

The third floor contained a bathroom, dressing room, and bedrooms for the use of members; also, steward’s apartments and kitchens.

The kitchens were fitted with ranges of special construction with two large hoists communicating with every floor in the building, with service lifts to the dining and other rooms. The large kitchen , larders and servants’ hall were put on the upper floor, and by a system of ventilation, allowed odours to be eliminated into the open air.

The Reform Club was heated by a high pressure hot water system, together with open fireplaces in the principal rooms, and electric bells fitted throughout.

The furnishings for the club, costing about £2,000, were supplied by Johnson and Appleyard of Leopold Street (as were the carpets), working to special designs submitted by the committee, all being in Gothic design, unvarnished oak, upholstered in hog skin and dark olive green tint, to match the building, including tables, chairs, armchairs and settees.

The building was illuminated with gas lights, provided by Guest and Chrimes, of Rotherham, with exception of the billiard room, where fittings were supplied by the Sheffield Gas Company.

Its members enjoyed the best cutlery, supplied by Brookes and Crookes, glassware by Webb and Sons, Stourbridge, and the dinner and tea service (with monograms of the club) by Doulton and Company of Burslem. Of course, the club enjoyed the best silver plate, manufactured by Otley and Sons, of Meadow Street, Wilkinson and Company, Norfolk Street, and George Warriss, based on Howard Street, providing the spoons and forks.

The Blind Institute fitted the club with mats and brushes, the ironmongery was by Chas Woollen and Company, with fire grates supplied by W.G. Skelton, and the fenders from Thomas Hague, both of Bridge Street. The hot closet in the serving room was made by J. Wright, and the ranges in the kitchen were by Newton Chambers and Company.

The Reform Club’s committee now reads as an historical list of local worthies: –

The Right Hon. A.J. Mundella, MP, was the President. The Vice Presidents were the MPs, Frederick Thorpe Mappin, Francis J.S. Foljambe (East Retford); the Hon. Henry Wentworth-Fitzwilliam, and William Henry Leatham (South West Riding); Lord Edward Cavendish, John Frederick Cheetham (North Derbyshire); the Hon. Francis Egerton, Alfred Barnes (East Derbyshire), and also Cecil Foljambe, of North Nottinghamshire.

The Treasurer was Samuel Osborn, with trustees made up from Thomas Wilson, John William Pye-Smith, Frank Mappin, Henry Ashington, and Robert Renton Eadon. The Honorary Secretary was George Walter Knox.

The club closed in 1942, with the Gladstone Buildings Company wound up in 1946.

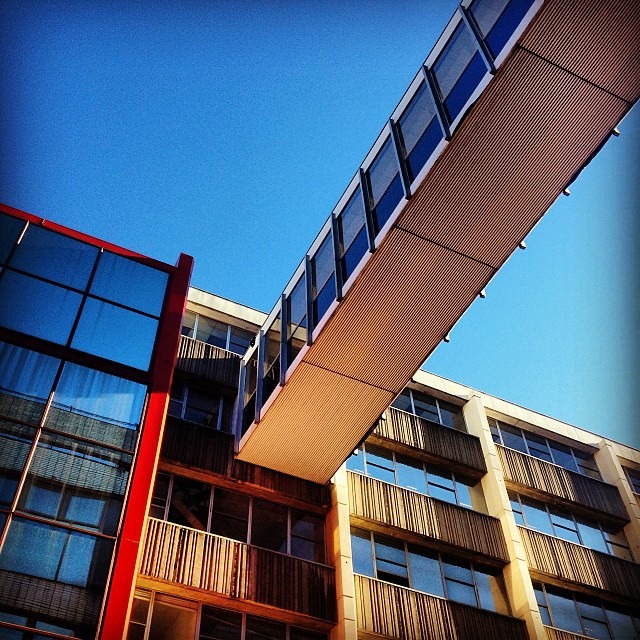

It all seems such a long time ago, and today No.1 St James’ Row comprises shops and offices, many available to let, and upper floor apartments.