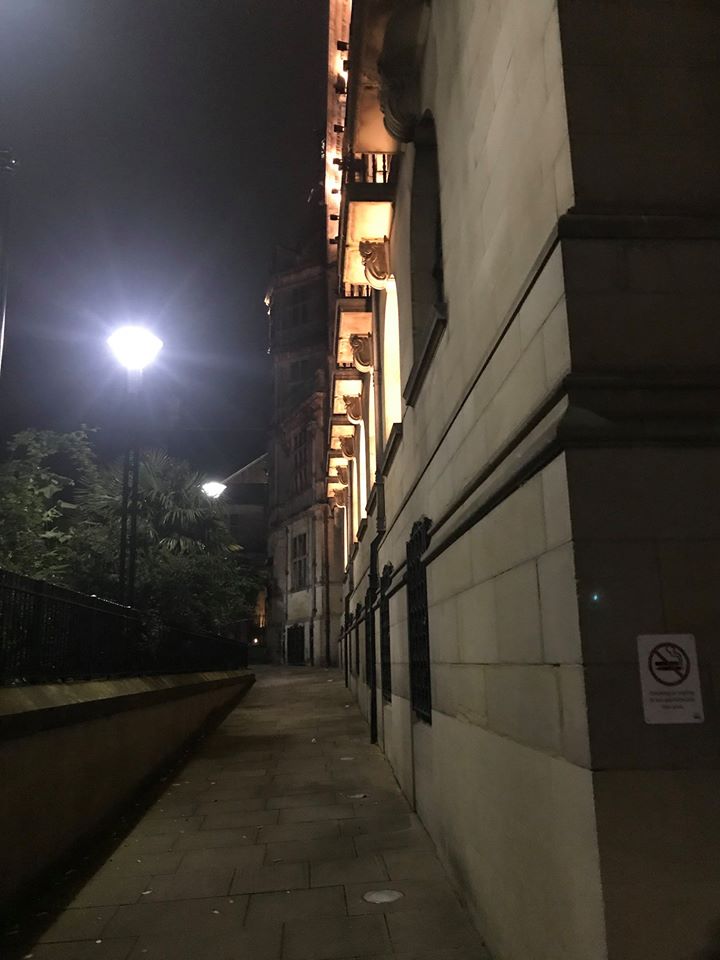

The grand old lady of Scotland Street is likely to be demolished soon.

The Queen’s Hotel, a relic of defunct Sheffield brewer, S.H. Wards, has been closed since 1997, boarded-up and decaying to the point of no return.

A planning application is expected to be submitted to Sheffield City Council, requesting the demolition of the inter-war pub, and replacing it with an eleven-storey apartment block.

There have been false dawns since the Queen’s Hotel’s closure. In 1999, plans were submitted, later withdrawn, to turn it into a massage parlour, sauna and health suite. Eight years later there were proposals to refurbish the old pub and create 126 apartments behind, but the scheme never got off the drawing board.

When the inevitable happens, it will end 128 years of a public house being on the site.

Scotland Street itself dates from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, built along a former boundary of an open field system. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, small factories, workshops and housing were built in the area, encouraged by an influx of Irish immigrants during the 1840s.

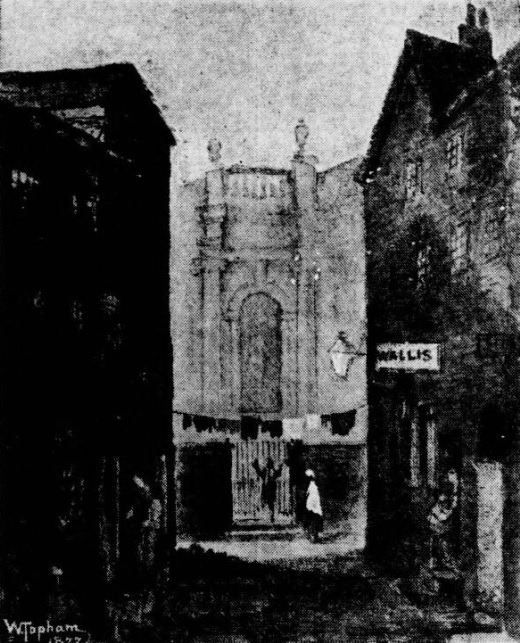

The public house was built in 1791, known as the Queen’s Inn, later Queen’s Hotel, complete with Dram-Shop, and a “good quoits and marble alley, and a very superior organ.” It belonged to local brewer William Bradley & Co, and subsequently by S.H. Wards, which bought it in 1876.

One of its longest serving landlords was James Bower Wragg, a well-known local angler, who reigned for fifty years or so, falling foul of the law on many occasions for serving outside permitted licensing hours.

By the 1920s, the Scotland Street area contained some of the city’s worst slum housing, described as “hovels of the aristocracy” and “mansions of the poor.” It prompted Sheffield Corporation to demolish large swathes of terraced houses.

The last tenants on the street were Charles Booth, 72, his brother Walter, 69, and their sister Eliza, who moved out in 1929. Their parents had moved into the house in 1856, when “Scotland Street was an eminently respectable street and one which many gay scenes were witnessed.”

Sheffield Corporation set about widening Scotland Street, and in the process purchased land from S.H. Ward & Co, including the site of the nearby Old Hussar public house, and part of the site of the Queen’s Hotel, on condition that they paid the brewery £2,875 towards the cost of rebuilding the Queen’s Hotel.

The new pub, built with stark, simple, exterior lines, opened in December 1928 with guest rooms on the upper floors, a large function room on the first floor and two ground floor bars. It became a popular haunt for factory workers, replacing the gap left by former residents, and was one of the brewery’s flagship establishments.

Scotland Street became one of the city’s strongest manufacturing areas, but a long-term lack of investment and a general state of decline, resulted in the area becoming down-at-heel by the middle of the century.

Many local factories closed, and the decline accelerated in the 1970s, as did the fortunes of the Queen’s Hotel, not helped by S.H. Wards being taken over by Sunderland-based Vaux Breweries in 1972. The brewery closed in 1999, two years after the Queen’s Hotel had closed its doors for good in April 1997.

Remarkably, despite the onset of time, the building still shows old Wards branding outside… but probably not for much longer.