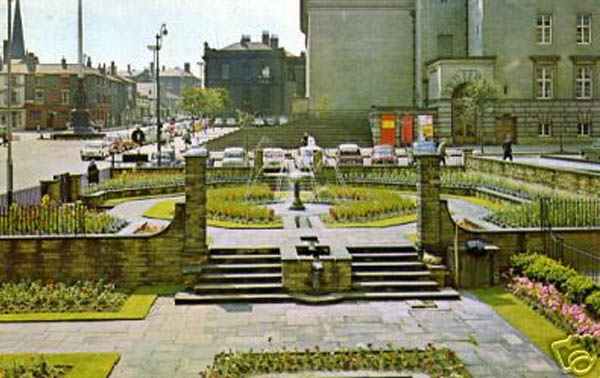

It is the “garden at the heart of the city”, and yet, the small plot at the corner of Barker’s Pool and Balm Green has never officially been named. It has been here since 1937, but these days most folk barely give it the time of day.

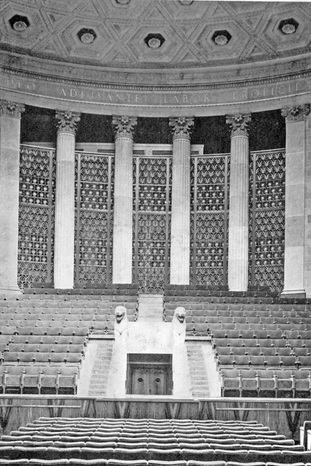

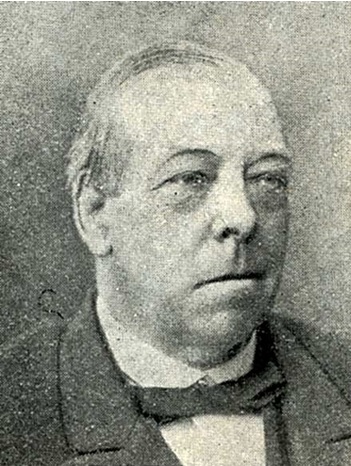

Barker’s Pool Garden, Balm Green Garden and Fountain Square are three of the names that have been attributed to it. However, when J.G. Graves, to whom Sheffield owes so much, attended the opening in 1937, he thought it unnecessary to give a name to the garden, but he had in mind its proximity to the City War Memorial.

“It will, I hope, provide a note of quiet sympathy which will be in harmony with the feelings of those who visit the War Memorial in the spirit of a visit to a sacred place.”

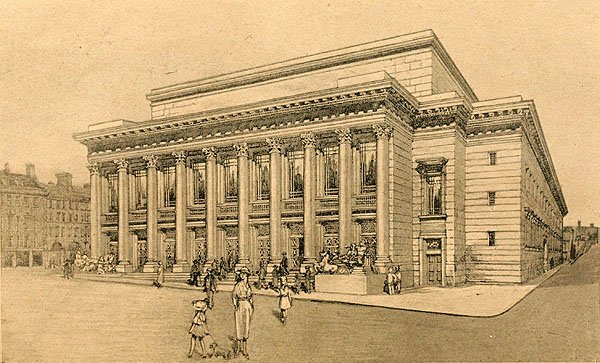

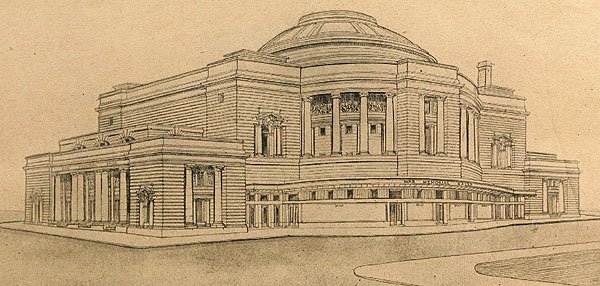

This garden, 400 square yards in size, would never have been created had it not been for the opening of the City Hall in 1932.

The land was owned by the adjacent Grand Hotel, the plot used as a car-park enclosed with advertising hoardings. But to J.G. Graves, it was an “eyesore”, obstructing the view of the splendid new City Hall from the Town Hall and the top of Fargate.

His solution was to negotiate the purchase of the land from the hotel. He paid £25 a square yard and outlined his plans in a letter to the Lord Mayor, Councillor Mrs A.E. Longden: –

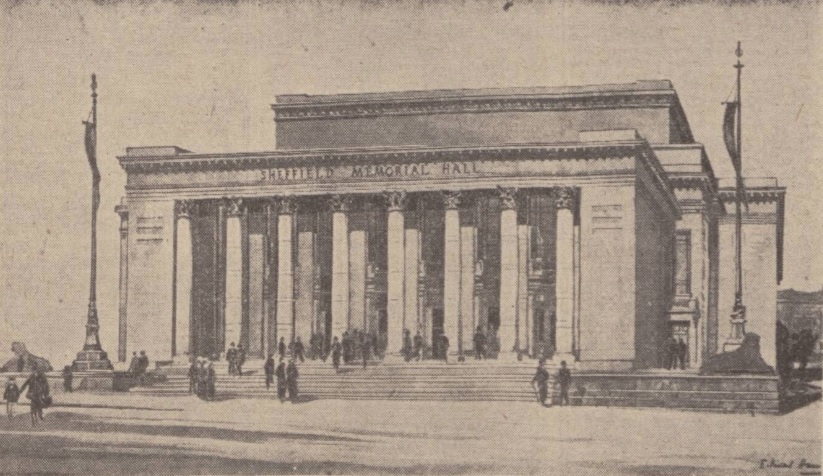

“When planning the new City Hall, the architect, in order to give due importance and dignity to the elevation, placed the front of the building at some distance from the existing building line.

“This, of course, enhanced the architectural appearance of the Hall, but has had the incidental result of obstructing a view of the Hall from Fargate and the Town Hall corner, as is partially done now by the hoarding which surrounds the intervening plot of vacant land, and if in due course a tall building should be erected on the plot referred to, the possibility of a view of the City Hall from Fargate and the Town Hall would be completely lost.

“I feel it would be a misfortune if, through lack of action at the present time, building developments should proceed which would permanently deprive the city of an impressive architectural and street view at its very centre.

“With this in mind, I have arranged to buy the plot of land in question at its present day market value, with the intention of establishing thereon a formal garden, already designed by an eminent firm expert in this class of work.

“With this explanation I have the pleasure of offering the piece of land as a gift to the city, together with the garden which I propose to have established thereon at my own expense, and with the condition that the garden shall be maintained by the Corporation in as good a state as it will be when it is handed over on completion of the work.”

The gift was a personal one, not connected with the Graves Trust, and duly accepted by Sheffield Corporation.

In 1937, the Grand Hotel announced proposals for extensive alterations and to place their principal entrance on Balm Green. The whole of the corner was now thrown open and the new garden would later adjoin the forecourt to the Grand’s main entrance, running from Barker’s Pool to the building line of the hotel.

To complete the scheme the Grand Hotel management decided to reface the whole of the side of the hotel with a material approximate to the colour of the stone of the City Hall.

The garden had been laid out by “a famous firm of garden landscapers,” railed off from the footpath, with a border of shrubs, crazy paving, a fountain, and a water runway to a lily pond, and various flower beds.

A huge crowd gathered for the official opening on August 3, 1937.

“We shall always be proud of this garden, because it is not only a gift for all time,” said the Lord Mayor. “I hope the garden will become a real garden of remembrance for the future generation, who could thank the beauty of mind and heart which prompted the gift.”

Of course, two years later, Britain went to war with Germany again, the symbolism of the garden perhaps lost on the despairing public. However, the garden has remained, although J.G. Graves’ conditions seem to have been forgotten by subsequent councils.

The fountain was eventually removed, the condition of the gardens fluctuating between mini-restorations, but its current state is a pale shadow of its original glory.

We might do well to remember the terms of J.G. Graves’ gift, although progress often comes into conflict with the past.

In 2019, initial plans were announced by Changing Sheffield action group (formerly Sheffield City Centre Residents Action Group) to create a unique space featuring ten large musical instruments and mini-trampolines, although the status of the application is unknown.