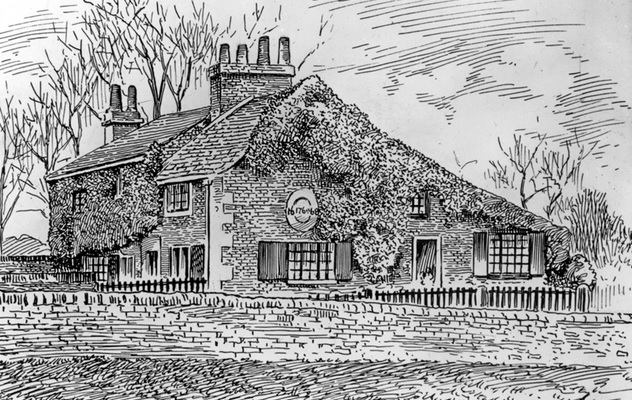

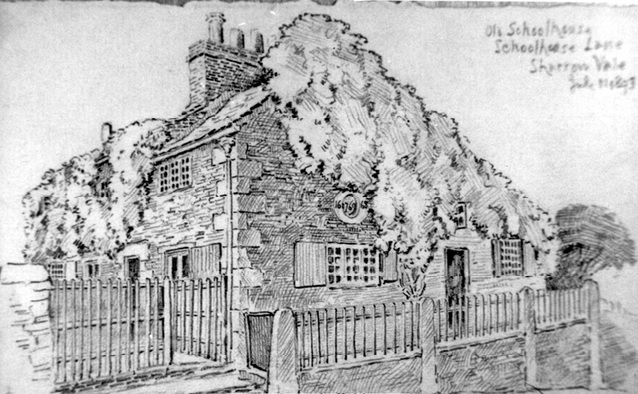

“Another bit of old Sheffield has disappeared. Over 200 years ago it stood ’distant, secluded, still’ away on Sharrow moor, with a beautiful rural country all around it, and Sheffield a comparatively long way off. But, like an invading army, Sheffield has been rapidly enveloping it in the last century. The city spread all around it. For a time, the town left it standing while it went on and on, seizing fields and woods, and filling them up with houses. Latterly, however, it has had time to turn back, and look around for spots that might have been passed and left unspoilt by bricks and mortar. And it has discovered quaint, old-fashioned Sharrow Moor School, a picturesque ivy-clad building, with its old-world air of simplicity and quietude, and its still rural surroundings. And down comes one of the few remaining bits of old Sheffield to make room for more of the all-devouring, up-to-date city.”

This expressive piece appeared in a local newspaper in November 1904.

Sharrow Moor School was one of Sheffield’s earliest schools. Originally a farmhouse, when erected in 1668, it subsequently became a charity school, and for many years boys and girls were taught to read and write, and some of them to learn mathematics.

In 1668, few houses dotted the landscape in this lovely valley. Its only neighbours were strewn far and wide across it. Beauchief Hall, Banner Cross, Whirlow Hall, Graystones, Whiteley Wood Hall, Broom Hall, Machon Bank, and Mount Pleasant.

In 1769 the building passed into the hands of the Rev. Thomas Savage, of Cherry Tree Hill, who extended it, and through his will it was destined to become a school.

His trustees were obliged to pay someone “four pounds, eleven shillings, and four pence for the teaching and instructing of eight poor children, born, or residing in or belonging to the parish of Sheffield, at a certain school situated in Sharrow Moor called Sharrow Moor School, to read the English language, two whereof to be taught to write, and account by being taught the first four rules in arithmetic. The sum of nine shillings and eight pence to be paid annually for the purchase of books.”

The school prospered under several masters – Mr Siddle up to 1860, followed by a Frenchman, Mons. Louis Theodore Elile Isensee, until 1865. Afterwards, ‘Daddy’ Whitehead took charge for 25 years until his death (the school referred to as Whitehead’s School) and it briefly closed before reopening in 1890 by Mr Haslam.

Then came the Free Education Act and the arrival of new schools at Hunter’s Bar, Pomona Street, Nether Green and Greystones, and the school closed. The money received from the sale of the land and building, together with its endowment, was transferred by the Charity Commission to find scholarships for children in the parish of Ecclesall, at the Sheffield Central, Technical, and Art Schools.

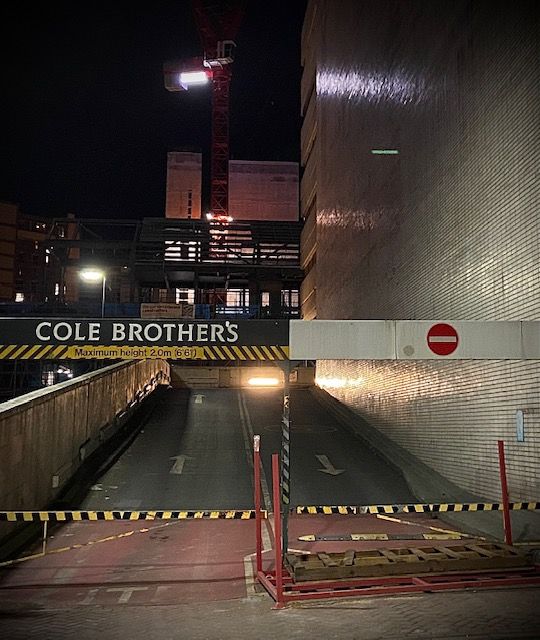

If it had survived, where would this forgotten treasure have been today? The answer is Bagshot Street, at Sharrow Vale.

© 2022 David Poole. All Rights Reserved