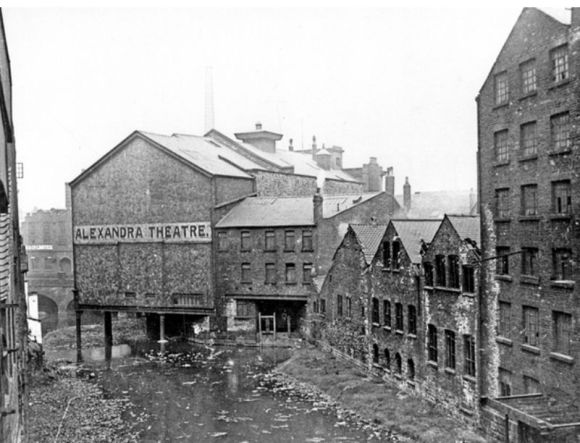

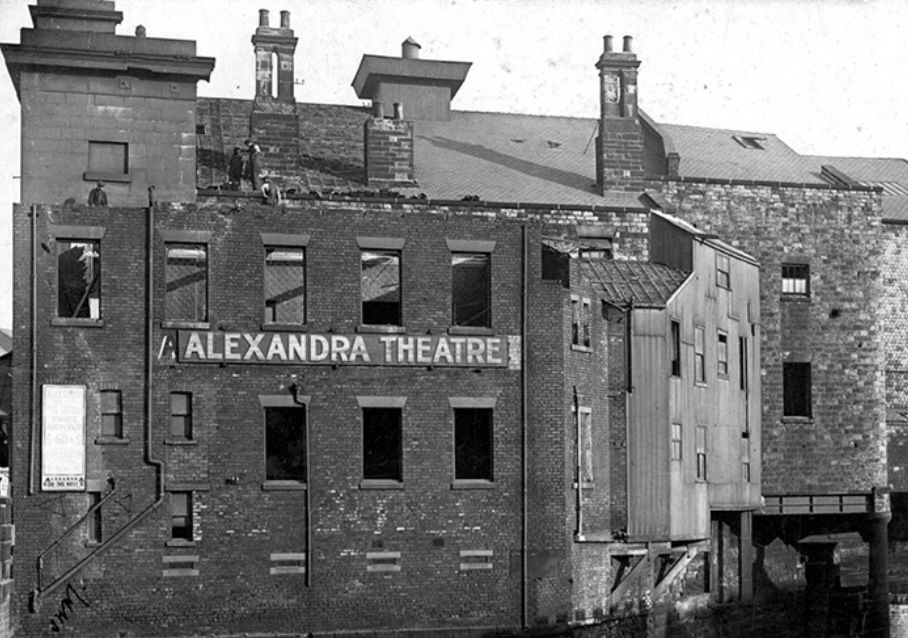

I recently posted about Alexandra House at Castlegate, which was erected on part of the site of the Alexandra Theatre that was demolished in 1914. Before then, Castlegate didn’t exist, and the theatre would have stretched right across the present road towards Blonk Street.

None of us can remember the Alexandra Theatre and it’s hard to imagine what it must have looked like in its heyday. It lasted only seventy-eight years but played an important part in Sheffield’s cultural history.

It didn’t start out as a theatre at all, but as a circus. The Victorian circus ring was different to today, providing a showcase for equestrian battle scenes, jugglers, clowns, female acrobats, and child performers.

The first record we have of a circus near the New Cattle Market at the confluence of the River Sheaf and River Don was in 1836 when John Brown laid the first stone. The building was designed by the architect James Harrison, Norfolk Row, and opened as the Royal Circus with ‘Tourniare’s Splendid Equestrian Establishment consisting of forty-two horses belonging to French, German, and Italian Equestrians.’

History books mention that it was built by Mr Egan, but this person has eluded me to the point that I’m beginning to doubt he ever existed. I can confirm that it was built for a company called Sheffield New Circus and Theatre and its interior was a copy of the famous Astley’s Amphitheatre in Westminster Bridge Road, London.

The shareholders were Mr Ryan (proprietor, a well-established equestrian, and circus owner), Mr Usher (manager, and former clown at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane), Mr Sambourne (solicitor), and Mr Harrison, the architect. By the following year, the shareholders were ready to let the circus on generous terms.

When Queen Victoria was proclaimed in 1837, there is reference to the spectacle seen at the circus: –

“The gay trappings of the soldiers on their richly caparisoned horses; the flags waving gently, the sound of music almost lost in the distance, and the dense crowd around the circle, made the view from that point very imposing.”

In April 1838, Mr Ryan announced the opening of a new season at the New Theatre Circus with upward of one hundred horses and a company of dramatic, pantomime and operatic performers.

While most Sheffielders referred to it as The Circus, it appears to have been known by several names. In those days, circuses were taken on seasonal leases by touring companies, and by 1839 it was advertised as Mr Batty’s Circus at the Royal Amphitheatre. A few years later it was the Royal Circus and by 1848 was called the Royal Adelphi Theatre under Mr Sloan who made significant changes.

“Considerable alterations have been made in the pit, and the middle of that hitherto dreary space is now fitted up with seats and protected from the cold by a close screen. By an admirable contrivance, the pit may be enlarged at pleasure. In its contracted state, a considerable number of persons may be comfortably seated; and if thrown open to the full size, hundreds more might find good accommodation. A new orchestra has also been constructed, and the whole house seems to wear a clean and lively, though yet unfinished, appearance. There is nothing striking or novel in the way of decoration; but in other respects, considerable efforts have been made to render the place more worthy of public patronage.”

Once again, the architect was James Harrison, and the building work was completed by Thomas Staniforth. “New Theatre! New Scenery! New Pit!”

The changes were made so that the Adelphi could show plays and compete with the only theatre in Sheffield, the Theatre Royal, but by 1849, it had proved unsuccessful, and the drama company dispersed.

Briefly known as the Theatre Royal Adelphi under Mr Cockrill, the lease passed to John Woodward who engaged Pablo Fanque’s Talented Troupe of Equestrians.

Pablo was a fascinating character, a Black man who started his own circus that toured across Yorkshire. In 1839, Pablo had spent the summer season with Andrew Ducrow’s troupe at Astley’s Amphitheatre and later toured with him.

In 1849, Pablo Fanque took on the lease for a year (not a season) at £200. He applied to magistrates for a theatre licence to perform stage plays but it was opposed by the owners of the Theatre Royal who claimed that one theatre in the town was sufficient (for a population of 130,000). To allow another theatre would have been to the detriment of both.

Fanque got his licence on the condition that he didn’t show serious drama but showed ‘spectacles’ that featured horses. The promise was kept for a brief time but soon there were performances of Othello, Julius Caesar, Richard the Third, The Merchant of Venice, and The Flowers of the Forest.

In 1850, a character called James Scott, a commercial traveller for a Leeds firm, bought the lease of the Adelphi from Pablo Fanque and managed to obtain a theatre licence.

By now, the Adelphi was owned by a consortium of eighteen people, headed by Dr John Carr, who was the Mayor of Sheffield in 1851.

Scott claimed that the owners had never drawn a shilling rent and that he had managed to turn a profit. When he left for another theatre at Derby, he stated that it was because the owners had demanded a greater share of the takings, but in truth, it was more likely because he’d been declared bankrupt in 1853.

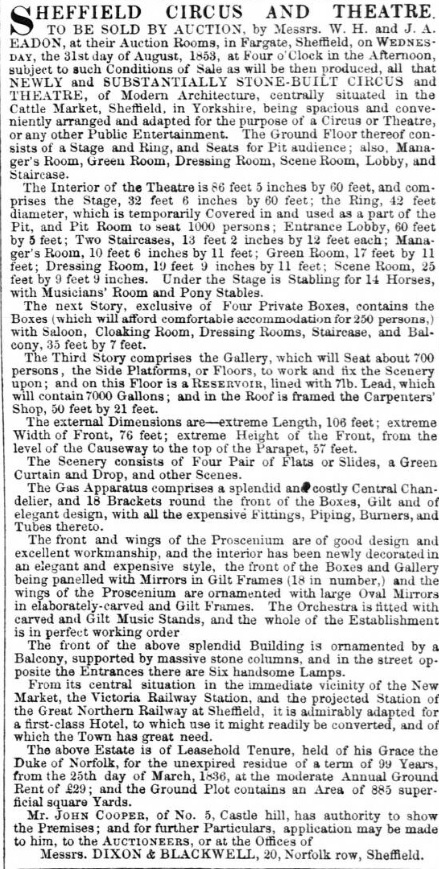

This was also the year that the theatre was put up for sale because it had never made a profit for its owners.

When it was rumoured, that Scott was returning to the Adelphi in 1859, the lease was quickly acquired by Thomas Youdan, the proprietor of the Surrey Theatre, in West Bar, who used it for storage of scenery and lumber.

Youdan made several unsuccessful attempts to obtain a theatre licence and contemplated turning it into a first-class concert hall, but for three years it remained dark and in a poor state of repair.

Youdan was born at Streetthorpe, near Doncaster, and had started as an agricultural labourer, before coming to Sheffield aged eighteen to work as a silver stamper for James Dixon and Sons. Abandoning the trade, he became the keeper of a beer house at Park, and then moved to an inn at West Bar called Spink’s Nest. He added music and singing to the public house and eventually became its owner, creating the Surrey Theatre with ballroom, theatre, concert hall, museum of curiosities, and a menagerie of animals from George Hunloke’s Wingerworth Hall.

When the Surrey Theatre burnt down on 25 March 1865, Youdan sustained a £30,000 loss, but was able to switch his business to the Adelphi Theatre.

He had it improved, cleaned its ‘black’ exterior, replaced all its fittings, and extended it with a stage house that was built on girders over the River Sheaf behind, and reopened it as the Alexandra Music Hall with accommodation for 3,000 to 4,000 people.

‘Tommy’ Youdan was a well-known figure and had a clever idea of what would please the Sheffield worker. He secured the most popular and exciting dramas and the cutlers and grinders, and steelworkers, thoroughly enjoyed a night at ‘Tommy’s.’

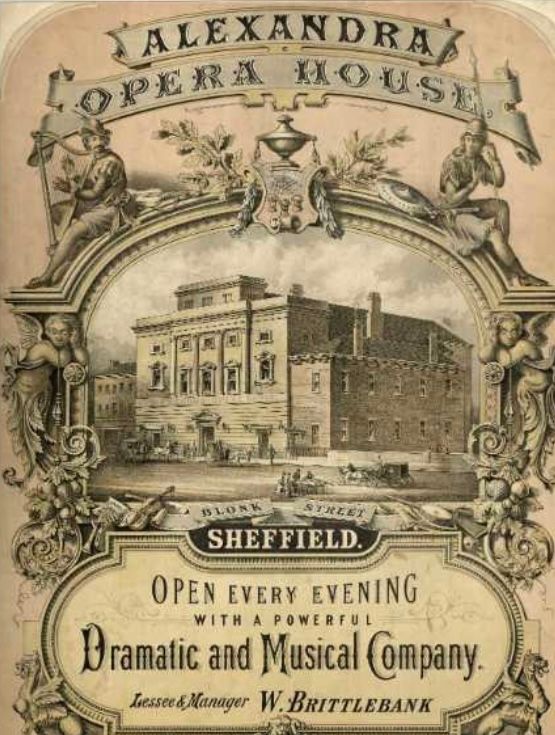

He was joined by William Brittlebank as manager and the two increased the prestige of the house of which they obtained a lengthy lease.

That was the commencement of more prosperous days with ballet and varieties, and on its boards appeared the stars of the day, including George Leybourne, prince of comedians; Sam Cowell, Arthur Lloyd, J.H. Milburn, and other celebrities. Sim Reeves also sang there and cursed the draughts from the river which flowed beneath the stage.

Youdan later renamed the theatre as the Alexandra Opera House, before retiring in 1874, and passing the lease to William Brittlebank.

During Brittlebank’s 20 years’ connection, such famous artists as J.L. Toole, Barry Sullivan, Charles Dillon, Marie Roze, Mrs Langtry, Charles Wyndham, E.S. Willard, Lewis Waller, Nelly Farren, Kate Vaughan, G.H. Harkins, and Henry Neville appeared in turn. The latter appeared in the best of the sporting dramas of Sir Augustus Harris from Drury Lane, and the pantomimes, too, were second to none.

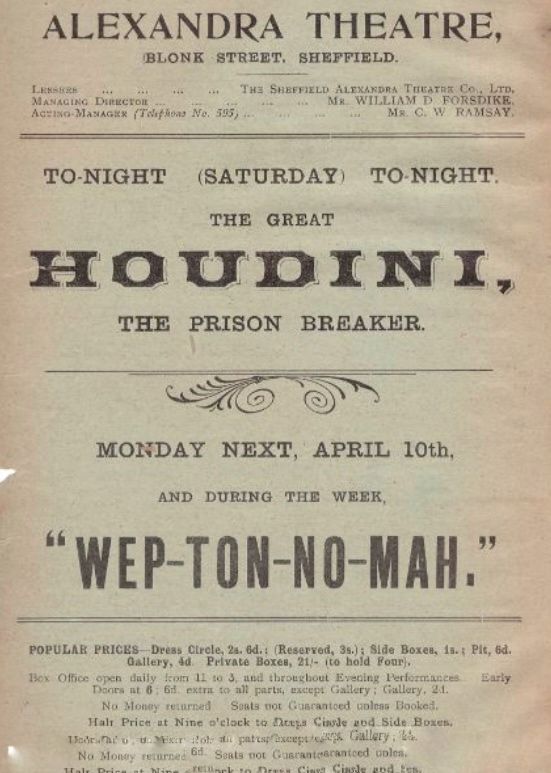

Brittlebank retired in 1895, and the theatre was taken over by a private company, with William David Forsdyke as managing director, who increased the seating capacity of the auditorium, and with a careful eye, watched the trend of public taste and catered accordingly.

He boldly advertised the Alexandra as the ‘People’s Theatre,’ and staged stirring domestic dramas and popular pantomimes that were originally produced in-house but were later sourced from London.

In this he was well aided by his acting managers, of whom none was more popular than C.W. Ramsey who managed it for the last ten years of its existence.

Ramsey had come to Sheffield as assistant to F.W. Purcell, then sole owner, and manager at the Theatre Royal. In 1904, on the death of the manager of the Alexandra Theatre, Ramsey was offered the job by W.D. Forsdyke, who was a well-known building contractor.

Pantomimes at the Alex usually ran from Christmas to just before Easter, and every Shrove Tuesday old folk were entertained and given gifts of tea, sweets, and tobacco. Ramsey also arranged nine benefits, usually under the patronage of the Lord Mayor and Lady Mayoress, Earl and Countess Fitzwilliam and other notables, and the programme was contributed by artists from all the other theatres in the city.

The ‘Alex’ closed on Saturday 28 March 1914, its fixtures and fittings auctioned, and afterwards demolished as part of Sheffield Corporation’s scheme for making a better approach from the centre of the city to the Victoria Station.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.