What is going to happen to Endcliffe Hall?

It was a headline that dominated local newspapers in 1913 when it was threatened with demolition. It might also apply to now, with the army planning to end its one hundred and ten year ownership of the large Victorian mansion.

In 1914, with Britain on the brink of war, Endcliffe Hall was bought by the Hallamshire Rifles (4th Yorks and Lancaster Regiment) and although the unit was disbanded in 1968 it remains the regimental Headquarters of Army Reserve Unit 212 (Yorkshire) Field Hospital.

A recent planning application asked for works to be removed ahead of the sale of the house and land. It is believed that the removal of a large painting called ‘Entering Fontenay’ and two glass fronted display cases, including the one for the Royal Army Medical Corps flag would require listed building consent, as part of the ballroom wall would need to be altered to take the items out safely.

What will happen to Endcliffe Hall when it is put on the market? This time around, demolition won’t be an option because it was Grade II* listed in 1973. I have an inkling that it might find a new life as a luxury hotel, although there might have to be extensions, thus increasing the number of rooms to make it viable.

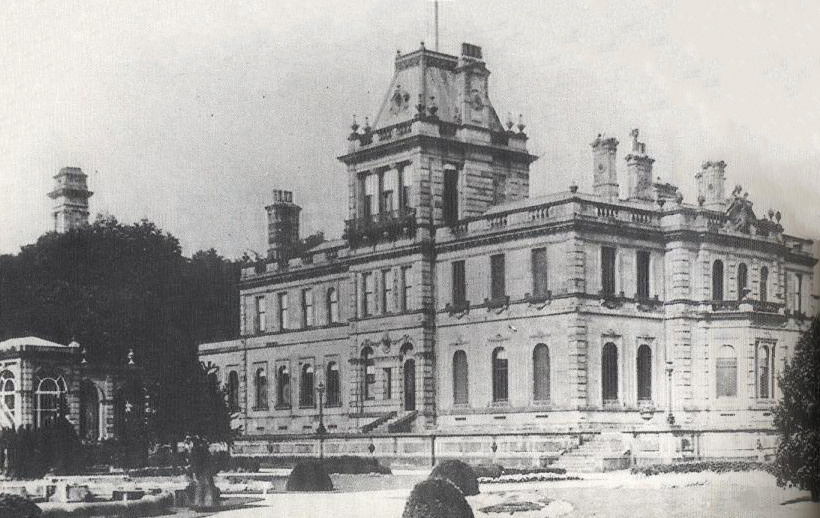

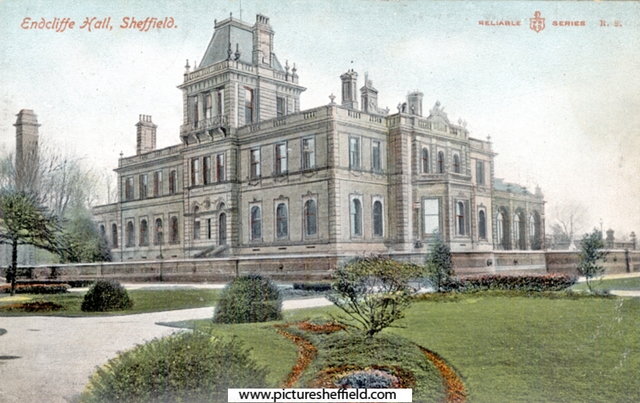

Endcliffe Hall is referred to as Sheffield’s biggest mansion – ‘The House Beautiful’ as the Sheffield Daily Telegraph called it in 1893. It was built between 1863 and 1865 by Flockton and Gibbs for the industrialist John Brown for a reputed £100,000 (that is about £10.6m today).

John Brown was born in Favell’s Yard, Fargate, in 1816, a part of the town favoured by people in good position for residence. His father wanted to apprentice the fourteen year old to a linen draper, but John disagreed. “I want to be a merchant, because a merchant trades with the whole world.” He was apprenticed to Earl, Horton & Co, cutlery manufacturers, in Orchard Place, and eventually took over the business.

In 1844, Brown moved into steel production on Orchard Street and Furnival Street manufacturing railway springs and files. His invention of the conical spring buffer brought him incredible wealth and allowed him to open further factories on Holly Street, Hereford Street and Backfields. These were later consolidated into one site – Atlas Works – in Savile Street.

Adopting the Bessemer process, Brown was a pioneer of the armour making industry, deciding that hammered armour plating could be rolled instead, and would receive orders to protect about three quarters of the ships of the Royal Navy.

In 1856, Brown became a member of the Town Council, an alderman three years later, and Mayor in 1861 and 1862.

John Brown married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Schofield, and lived comfortably at Shirle Hill (now Nether Edge) but with immense wealth, wanted to build a magnificent mansion. In 1863, when the Endcliffe Hall estate went to auction, Brown bought it and demolished the old hall (the second to have stood on the site) and replaced it with a mansion in the Italian style, with free use of the French interpretation. The only relic to survive from the previous hall was a piece of quaint animal carving that was fixed over the fireplace of the principal kitchen.

In those days, the house stood in countryside. “The air is pure, from the best source, the high moors. A lofty range of hills rising behind this south-eastern aspect, forming a grand and imposing background, sheltering it from northern winds. A view of Sylvan Scenery in the valley of the River Porter, and the wood-crowned heights of Brinkcliffe Edge. The eye is carried through the lovely Vale of Whiteley Wood, up to the Moorlands of Hallamshire. There is a plentiful supply of the purest water and building materials from the ground.”

John Brown employed Flockton and Abbott to design and carry out the 36 room mansion almost regardless of cost, and those gentlemen succeeded in producing a building which, for perfect architecture, excellent workmanship, unique domestic arrangement, and appropriate accessories, could not be surpassed in the provinces.

Nearly 300 workmen had worked on it and the proportions of all the rooms were said to be magnificent, with a light and cheerful appearance, and a sense of perfect ventilation throughout. On completion, in 1865, the house was, on the invitation of the architects, opened over two days for inspection, and on each day crowds of leading gentry and merchants visited to see it for themselves.

John Brown was knighted in 1867, and there is a saying that money cannot buy happiness. In hindsight, one wonders whether John Brown and his wife were truly happy at Endcliffe Hall. A year later, Brown denied that he had sold the estate, the rumour fuelled by their desire to spend the winter months in Torquay, and only returning to Sheffield in the spring. Sir John and Lady Mary both suffered ill-health, and it is only during research for this post that we can now speculate that his ailments were due to his mental health.

In 1871, the John Brown Co had set up its subsidiary —the Bilbao River and Cantabrian Railway Company Limited— and bought plots in Sestao (Bilbao), Spain, to construct blast furnaces and process iron ore from the nearby Galdames mines they owned, which was to be transported by a factory owned railway they started building that same year. The railway was finished in 1876, and blast furnaces were completed in 1873. The political climate —the third Carlist War [1873-76] and its aftermath— are one of the reasons which motivated the company to abandon the blast furnace project and sell the installations to the Duke of Mudela —Francisco de las Rivas— in July of 1879. The second and more important reason for selling its processing plant was the fact that ore deposits in Galdames were significantly less than prospected. It was lamentable that Sir John’s career should have been so clouded owing to heavy losses in the Bilbao project.

Lady Brown died from a painful disease in 1881, and Sir John gradually withdrew from public life, his health deteriorated, and he spent increasing amounts of time in southern England. He left Endcliffe Hall for the last time in 1892 and two years before his death in 1896 had been declared legally insane.

Rumours circulated as to the future of the estate. Some suggested that it would remain in local hands, others speculated that it was being split up for building plots, while a third rumour suggested that the Duke of Norfolk might buy the house. Certainly, an enquiry was made but never followed up.

The sale of Endcliffe Hall had been put in the hands of London-based Maple and Co, and in January 1893 it offered Sheffield Corporation the chance to buy it for £70,000. The amount of money involved and uncertainty as to what to do with it meant that the corporation politely declined. Neither had there been any other offers for the estate.

Maple and Co sent the entire contents of Endcliffe Hall to auction in April 1893. “The best of furniture, the richest of appointments, the costly statuary, bronzes, pictures – the art treasures collected through many years – are to be scattered far and wide,” the Sheffield Daily Telegraph reported. The contents raised between £9.000 and £10,000 and were believed to have been sold for about a third of their cost

“In local eyes it was the embodiment, in stone and lime, of a career unique even among merchant princes and manufacturers. Next week the beautiful home will be desolate; its costly contents, collected from all quarters, dispersed under the hammer, and no doubt not a few Sheffield families will in days to come treasure in their lares and penates some relic of the most complete and perfect amongst the many pleasant dwelling-places reared by the Men of Mark in our midst. Surely the goodliest habitation within our borders, its masonry fair of face as the day one stone was laid upon another, will not come down in the cutting up of the gardens and grounds, the terraces and parks, to make way for rows of villas to be raised by the speculative builder.” – Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Sat 15 April 1893

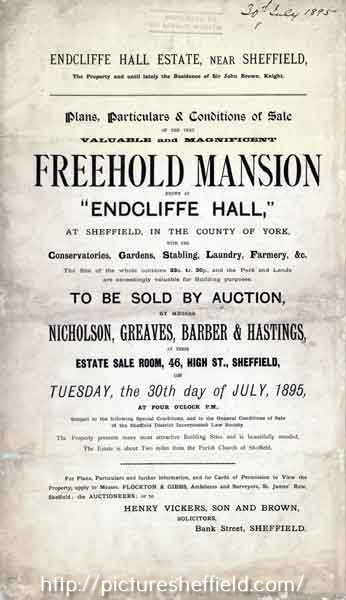

In July 1895, Endcliffe Hall and the estate went to auction at Nicholson, Greaves, Barber, and Hastings. It was bought for the knock-down price of £26,000 by a secret syndicate of eight local gentlemen. Their identity would later be revealed when the Endcliffe Hall Estates Company Limited was formed, with the directors named as Henry Herbert Andrew, J. W. Barber, Robert Colver, Robert Abbott Hadfield and William Samuel Laycock, with John Wortley as secretary. A large portion of the estate would be sold for building quality residences, but the future of the house remained in doubt.

The company adopted a scheme prepared by H.E. Milton, of Westminster, for laying out a new housing estate and plans were subsequently submitted to Sheffield Corporation for Endcliffe Grove Avenue, Endcliffe Park Avenue, and Endcliffe Hall Avenue.

Whilst grand new houses were built on parts of the estate, the Endcliffe Hall Estates Company used the mansion and remaining grounds as an entertainment venue. It operated between 1896 and 1913 and was used for meetings, ceremonies, dances, dinners, weddings, exhibitions, fetes, bazaars, and even as a location for several Shakespeare plays.

“The wealthy man of the West End desiring to invite his friends to dance, dinner, or concert, have turned to Endcliffe Hall as a place affording accommodation often superior to that available at his own house, and a place presenting many advantages over a hotel by reason of its privacy and its situation in the principal residential district of the city. He has been able to entertain a large party with as much success as if they were at his own home, and without subjecting himself to those little inconveniences and disturbances which he would have suffered if his own home had been used. All the worry of arranging rooms has been lifted off the shoulders of the host and hostess when they have gone to Endcliffe Hall.”

Like many large houses, the upkeep of Endcliffe Hall proved to be a problem for the company. Income from these events did not cover the upkeep of the house, and it attempted to close it in 1906, but met with opposition. Charles Burrows Flockton, from the well-known dynasty of Sheffield-based architects (which had designed the house), proposed setting up a company to purchase the hall and carry on as an entertainment venue or country club. In the event, the company chose to keep the hall and persevere, but failed to make it a success.

In 1913 it decided to sell the house and the remaining five acres of land that remained unbuilt, but with no buyers forthcoming, it proposed demolition. Once again, there was opposition and C.D. Leng, of the Sheffield Telegraph, campaigned to try and save it for the use of residents in the West End. He sent out thousands of circulars and reply postcards pleading for subscriptions to buy it. Leng decided that it would cost £60,000 to buy, and the whole place could be taken with a ground rent of £300. He proposed the addition of a stage in the ballroom for theatrical performances and there would also be room in the grounds for tennis, croquet and bowls.

Despite Leng’s efforts, the surveyor for the Endcliffe Hall Estates Company revealed that he had received an offer from another source. It was understood that the hall was going to be bought by solicitor Branson and Son on behalf of some Sheffield gentlemen who intended to retain it for public use.

It was actually a smokescreen because Colonel George Ernest Branson was commanding officer of the Hallamshire Rifles and wanted to transfer the officers and men from the cramped, ill-adapted, and inconveniently situated barracks at Hyde Park to Endcliffe Hall.

The purchase was approved at a meeting of the West Riding Territorial Association at York in January 1914 and cost £10,000 with the vendors agreeing to spend £2,000 on internal alterations and repairs, and the stables and coach houses were converted to become the drill hall for the regiment.

Of course, Britain would soon be at war, and during World War One, Endcliffe Hall was used as a hospital with eight indoor wards for 120 patients, and 32 beds in the ballroom. An open air ward was added on the site of the former conservatory.

And so we come to the present day with the overall aim of the RFCA being “to sell the Endcliffe Hall site, including all land and buildings, thus bringing the Army’s 100 years of occupancy and ownership of the site to a close.”

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved