The biggest surprise is that it wasn’t until 1985 that the Peace Gardens were formally named. Created in 1938, originally called St. Paul’s Garden, the name was at first suggested, then adopted by the people of Sheffield. It appears that nobody was in any hurry to suggest anything different.

But it wasn’t the case in the beginning.

The gardens stand on the site of St. Paul’s Church, demolished in 1938, when inner city slum clearance resulted in falling attendances. Quickly swept away, Sheffield Council laid out pathways, flower beds and grassed areas within the old churchyard walls.

It was a short-term solution, the council buying the land for £130,000, and designating it for a proposed Town Hall extension.

The name, Peace Garden, was proposed in response to the Munich Agreement.

This was a treaty, concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, France and Italy, that allowed Germany to claim the “Sudeten German territory” of Czechoslovakia. Most of Europe celebrated the agreement, because it prevented the war threatened by Adolf Hitler, who had announced it was his last territorial claim in Europe, the choice seemingly between war and appeasement.

The country thought that war had been averted, a pretence, because hostilities started a year later.

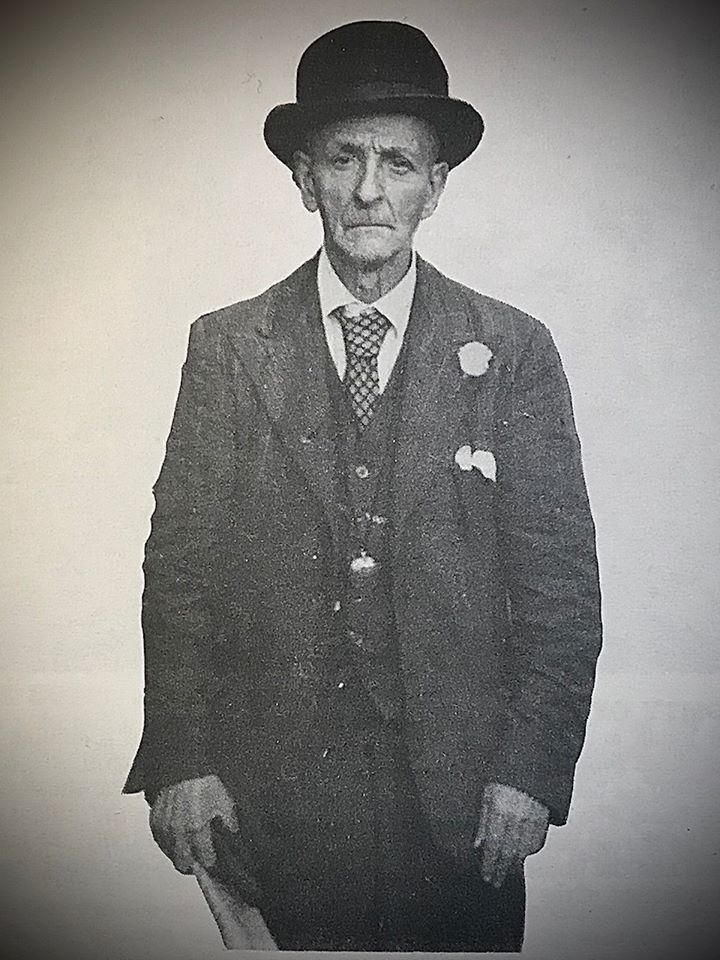

The name was suggested at a formal dinner by Alderman Ernest Rowlinson, the proposal immediately mocked by Mr Slater Willis, who thought it would be taken by many to mean the commemoration of Charles Peace, the Sheffield-born burglar and murderer.

There were critics of the garden scheme, Herbert Oliver, standing as Progressive candidate for Crookesmoor said, “I would rather we built 5,000 homes for old age pensioners than use the money making a garden on St. Paul’s site.”

An offer had already been made that the grounds of Brincliffe Towers at Nether Edge, a gift to the city by Dr Roger Styring, should be used as a Peace Garden instead.

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph was also cynical, writing that, “As for peace, this has never, since the Great War, been in graver danger.” It also suggested a better name – “the Appeasement Garden.”

But the Peace Garden name stuck, and after completion there were congratulatory comments in local newspapers.

“There isn’t much to be proud of in the centre of the city so far, which will render this garden the more surprising and impressive to strangers,” said one correspondent.

Bob Green said that, “The Peace Garden is a boon to old age and workers of the city at dinner hours. I’ve been informed that the garden is only temporary. But I hope the garden will continue and not be built on. I say, ‘Long Live the Peace Garden’.”

Another said, “May I suggest that the garden is illuminated or floodlit at night, also a drinking fountain, and a few more seats would be welcome.”

A year later, the city’s residents seemed satisfied with the Peace Garden, and even the Sheffield Evening Telegraph had changed its tune.

“The suggestion that it should be called the Peace Garden was received with ribald mirth. Whatever its official title may be, it is undoubtedly a delightful and peaceful spot, rich with flowers.”

But there were worrying developments that would blight it for decades to come.

“This morning at 8 o’clock it looked like a battlefield. Seats were overturned and the whole place a disgrace. Last week the gardener put in some thousand bulbs and the next morning most of the beds had been trampled on.”

Another correspondent also expressed concern. “I have occasion to come through this morning before the cleaning process begins and it is not a pretty sight – cigarette ends, empty cigarette boxes, matches, and matchboxes, waste-paper round each seat, and a lot of it blown to the grass.”

And there were still critics of the scheme.

“It may surprise a good many to know that the garden is going to cost this generation, and the next, just about £6,000 a year, quite apart, or rather in addition to upkeep, gardeners’ wages, renewals and the like. That is £16 a day in order that a few people may sit there for about seven or eight weeks in the year.”

The Second World War curtailed any plans for Town Hall expansion, although the ‘Egg Box’ extension appeared nearby in the 1970s.

The Peace Garden, or Peace Gardens as they became, survived the war and became subject of civic pride, all-year round planting schemes, grass to lay on and a place to sit and talk.

However, the garden also attracted undesirable characters – the homeless, drunkards and unruly gangs.

When the Heart of the City project came about during the 1990s the Peace Gardens were at the centre of the scheme. In 1997-1998, they were redesigned by the council’s Design and Property Services, a series of water features, pathways, balustrades and artworks, built in Stoke Hall sandstone, the same material used in the Town Hall.

The new garden, without traditional flower beds and less maintenance, were slightly sunk to mask the noise of buses from Pinstone Street.

Its centrepiece is the Goodwin Fountain, 89 individual jets of water, dedicated to Sir Stuart and Lady Goodwin, and the Holberry Cascades, named after Chartist leader Samuel Holberry, including eight large water features located on either side of the four main entrances.