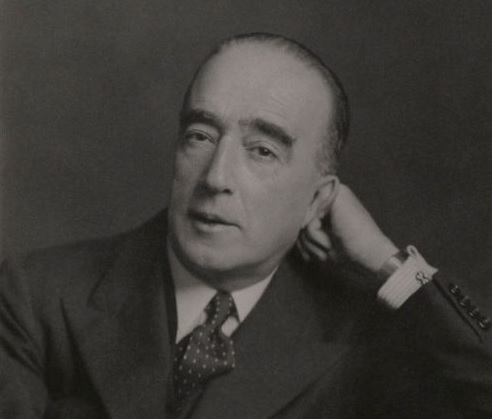

Following Michael Grandage’s departure, the Artistic Director’s role at Sheffield Theatres was one of the most sought after jobs. The role went to Samuel West, son of Timothy West and Prunella Scales, and born into the acting business.

At prep school, the boy Samuel made his debut playing Claudius in Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. It was seeing his dad play Shakespeare’s Claudius to Derek Jacobi’s Hamlet at the Old Vic a few years later that settled his choice of career.

“People clapped loudly,” he said recently, “and I thought ‘I’d like to do this’.”

He read English at Oxford and moved into a career that combined classical theatre with British movies (Howard’s End, Iris, Carrington, Reunion, Jane Eyre, Notting Hill, and Van Helsing), TV and radio. His London stage debut was in 1989 in Les Parents Terrible and was a success in Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia at the National Theatre in 1993. He later spent two years with the Royal Shakespeare Company.

West made his directorial debut with The Lady’s Not for Burning at the Minerva Theatre, Chichester in 2002 and succeeded Grandage at Sheffield Theatres in 2005, reviving the controversial The Romans In Britain and As You Like It as part of the RSC’s Complete Works Festival.

Several of his acclaimed productions perhaps proved a little too controversial for the people who held the financial purse strings, and there might have been conflict as he battled the dramatic “powers that be.”

When the Crucible closed for its massive refurbishment in 2007, he had hoped that the Crucible might continue with touring productions, but relinquished his role when the theatre fell silent.

“Two years is never long enough to spend at a great theatre like this and my plans being turned down was the only reason I decided to leave.

“When the building is closed, I believed, and still believe, we should make attempts to produce outside the theatre, with co-productions, found spaces, bringing back old shows that had served us well and doing West End seasons – all those sort of things – partly because it’s important to keep audiences alive in a city where you’re the only theatre.”

West said he did not believe board members were against his aims but that their financial plans prevented them from making “promises which they couldn’t later fulfil.”

He rekindled his association with the Crucible in 2017 when he returned to play Brutus in Julius Caesar.

“I’ve missed it. I think Sheffield is a great city and it’s really nice to see some friendly faces who seem quite pleased to see me.”

We know West for his TV roles – Midsomer Murders, Waking the Dead, Poirot, Any Human Heart – and big roles in Mr Selfridge and Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell.

However, his biggest role is playing Siegfried Farnon in the two series of Channel Five’s recent revival of All Creatures Great and Small.