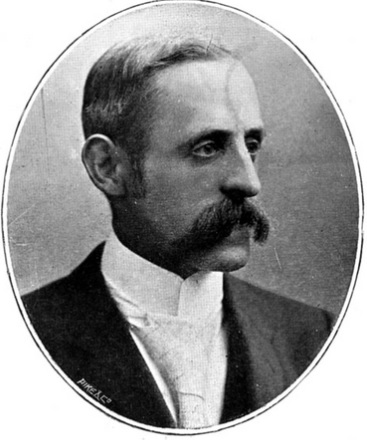

Sheffield had fine architects, and the name of Herbert Watson Lockwood should be amongst them. He was responsible for the Young Men’s Christian Association Buildings on Fargate (known to us as Carmel House), the Pupil Teachers’ Central Schools on Holly Street, Ruskin House Training Home for Girls at Walkley, as well as churches and school buildings.

Born at Derby in 1853, he was the son of Jonathan Lockwood, a staunch methodist, and educated at Sheffield Royal Grammar School before training as an architect and surveyor. He practised in Sheffield for twenty five years, first on York Street, then Church Street, and finally at Palatine Chambers on Pinstone Street. His reputation amongst his fellows was such that he became a fellow of the Sheffield Society of Architects.

In 1891, Lockwood submitted plans for the competition to build the new Town Hall but failed to make the shortlist. According to The Builder, his plans were superior to Edward William Mountford’s winning design. A couple of years later he was amongst a group from Sheffield which visited the Chicago World’s Fair.

Lockwood’s biography appeared in Sidney Oldall Addy’s Sheffield at the Opening of the Twentieth Century, published in 1901, and, aged forty-eight, he was at the top of his game.

In 1903, Lockwood became a director of Ellis and Webster Ltd, general merchants, with premises on St Paul’s Parade. The company had started in 1901 as a partnership between two jewellers, Evenio Ellis and Robert F. Webster, but Ellis left when it became a limited liability, leaving Lockwood to become its chairman.

The fortunes of Ellis and Webster make painful reading, and it was soon apparent that the company was struggling. Lockwood had agreed his fees at £90 per annum but received nothing. With property worth £4,000, he advanced a similar sum to the business and guaranteed, along with other directors, trade accounts and bank overdrafts amounting to £5,156.

In 1905, Lockwood raised securities to partially pay off his bank overdraft but a year later realised that he was insolvent. It didn’t stop him providing guarantees on debts contracted by Ellis and Webster amounting to a further £200.

Inexplicably, by the time he was declared bankrupt in 1908, it was apparent that Lockwood hadn’t paid any attention to his architectural practice for three years. His liabilities were £5,579, and assets of £96, with his own debts amounting to £4,598 (that’s about £693,000 today). The judge at his hearing said that it was, “The supreme folly of a gentleman in a good position as an architect financing a business of which he knew nothing and being led into bankruptcy.”

Lockwood lost everything, but what happened afterwards is subject to speculation. The official receiver had been negotiating with Lockwood’s relatives in America and his creditors settled by the end of the year.

It was almost certain that salvation came from his brother, Arthur James Lockwood, who, aged twenty-one, had travelled to Buffalo, New York, as an apprentice at Arthur Balfour, and had risen to become chairman of several steel concerns.

As for Herbert Watson Lockwood himself, he disappeared from public view. The 1911 census records him as an architect and surveyor, working from the old family home at 17 Winter Street.

But his reputation was ruined, and four years later, we find that Lockwood had moved to the United States to be with his brother, living in Essex County, New Jersey. Alas, the date of his death remains a mystery, but I’m sure that somebody will be able to provide this missing detail.

Remember Herbert Watson Lockwood the next time you walk up Fargate, and see his surviving legacy to the city, from a man destined by circumstances not to succeed.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved